Britannian History

Early Medieval Dress.

Early Medieval Dress."449 In this year Mauricius and Valentinian obtained the Kingdom and reigned seven years. In their days Hengest and Horsa, invited by Vortigern, King of the Britons, came to Britain at a place called Ebbsfleet at first to help the Britons, but later they fought against them. The king ordered them to fight against the Picts, and so they did and had victory wherever they came. They then sent to Angeln; ordered them to send them more aid and to be told of the worthlessness of the Britons and of the excellence of the land. They sent them more aid. These men came from three nations of Germany: from the Old Saxons, from the Angles, from the Jutes."

So wrote a monk in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles many centuries ago. The fifth to ninth centuries were some of the most turbulent of British history. This was the time when England was born, the time of Hengest and Horsa, King Arthur, Beowulf, Redwald of Sutton Hoo, St. Augustine, King Offa, King Alfred, the Viking Invasions and the foundation of the English church.

Angelcynn (pronounced 'Angle-kin') is an Old English word meaning 'the English People'. the Angelcynn is a living history society which aims to recreate, as authentically as possible, the richness of the birth of a nation which has passed into legend and into lore.

Gunnas to Houppelands

A Thousand Years of English Dresses

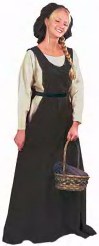

What do you see when you think of typical Medieval clothing? Do you think of flowing pink dresses with pointed princess hats? Since the Middle Ages lasted a thousand years, there were a lot more types of dresses. This paper will trace fashions for women's clothing in England for the fifth through fifteenth centuries. The Middle Ages started in England during the fifth century. The Saxon period (from A.D. 460 to A.D. 1066) had a distinctive style of dress.

The first garment is the tunica. It was a fitted underdress, usually made of linen. It had long tight sleeves and the skirt reached to the floor (Evans 120). Over this was worn a gunna, or gown. It was fitted also and had sleeves that reached only to the elbows. The hem was tucked up on the right side into an embroidered leather belt. Saxon women did this to show off the bright material of the tunica. Customs often create a demand for new fashions. Saxon custom "decreed that the locks of the fair Saxon woman be entirely concealed" To do this, many Saxon women wore headrails. Headrails were two and a half by three quarter yard strips of linen or silk that were drawn from the right shoulder over the head and to the left shoulder.

During the latter part of this period, the ninth and tenth centuries, the tunica began to change. The sleeves flared out extravagently. They also gained bands of decoration. The trend was toward barbarian extravagence. The Norman invasion changed the trend of English fashion, as an invading army usually does. The ideea was for elegance, simple yet expensive. One thing the invasion changed was the name of the overdress. It was now called a bliaut. It was tight at the top with a very full skirt. The sleeves were still very wide. It was not made of one rectangular piece, like the earlier dresses. The top, or bodice, was sewn to the skirt. It was a dress made to show off the body, not hide it.

The major change in the twelfth century was the sleeves. They were now narrow until the elbows, or sometimes the wrists, and then widened out so far that they dragged on the ground. To deal with this, women would often tie up their trailing sleeves. Consequently, tied sleeves became the fashion. Fashion is often influenced by necessity. The late twelfth century introduced parti-coloring. Parti- colored clothing was made of two or more colors or patterns of material making up different halfs or quarters of the garment. Parti-coloring lasted until the end of the Middle Ages and is often considered to be a typical Medieval fashion.

The next century, the thirteenth, is "remarkable for its simnplicity and grace" It, and the fourteenth century, are also remarkable for their tight and fitted styles. The button was the innovation that brought about the fitted style. Brought back by the Crusaders, buttons made it not necessary foir dresses to be loose enough to be pulled over the head. The waist could be tighter than the shoulders with buttons. Also gussets, wedge shaped inserts that increase movement, made tight fitted dresses practical.

As a result, the cotehardie became the fashion. It was a fitted dress that flared out at the hips or waist. The sleeves extended to the wrists or to the knuckles. An underdress was worn underneath the cotehardie and would peek out at the neck or sleeve edges. It was a style designed to show off how tight your tailor could sew your dresses. Over the cotehardie was sometimes worn a sideless surcoat. The sideless surcoat was sometimes called the Gates of Hell. It consisted of a narrow bib attached to a full skirt. It was often trimmed with fur. The belt was worn over the cotehardie, and not the surcoat. This ephasized one of the major parts of this period, slim hips.

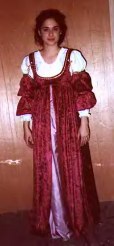

"From 1350 to 1380 all women of fashion were to be seen with tippets at their elbows." Tippets were not little dogs; they were strips of fabric attached at the elbow to the sleeves of cotehardies. They were very long and hung down to the knees. They emphasized another focus of this period, the vertical line. The trend in the fifteenth century went the other way. Width was now the emphasis, not slim and vertical. It was now stylish to have wide hips and voluminous sleeves (Houston 159). The new style of dress was called a houppeland. The bodice had a deep V-neck that showed off the shoulders. The skirt was enormous and attached to the bodice above the hips. It was fashionable to be a big woman.

The most obvious feature of the houppeland was its sleeves. They no longer hugged the arms, but were instead very baggy. Wealth was shown by how much material you could waste in baggy sleeves. Another common characteristic of the houppeland is dagging. The edges of sleeves often had scalloped edges called dags. The purpose of fifteenth century fashion, showing off wealth, was done with dags since it also wasted a lot of fabric.

Hairstyles and headdresses

As there were variations in clothing, so there was in hairstyles. For men, this is relatively simple, long or short hair, curled or straight, beards or clean shaven. Some beards were curled and separated into two thick pieces, but this was more favoured by royalty than by the majority of the populace. For women, however, there were several different styles available, and just as much argument about this as anything else!

In 1250-1260, hair nets, wreaths of flowers, and veils were worn by women. The lady at the forefront of the Blessed of the statues at Bourges has neck and ears visible under short curls at the temple. A tressure, which is a pair of long plaits, around the head, was held in place by a snood. Also from this time, although ending its popularity in 1300 was the crespine. This was worn as a mesh over the hair, generally of silk, studded with jewels at the intersections of each piece of silk. The hair was coiled in plaits or coils around the head, and worn under the crespine. "From 1200 until nearly 1300 the hair, still parted in the middle and braided, was drawn back and cris-crossed into a bun usually rather low on the nape, from 1250 this was covered with a colored net. When the hair had been arranged thus, a piece of white linen was brought from under the chin to the top of the head and there pinned; then a band of stiff linen was pinned around the head. Instead of a band, there might be a complete cap, like a bell-hop's. " (The cap resembles more of a pill box style of hat than a bell hop's cap, but that's personal interpretation.)

The crespine is the relative of a much older garment. In her public lecture, Proffessor Elizabeth Barber, Proffessor of linguistics and textiles at the Occidental University, Los Angeles says that in 6500 BC, a garment was found much resembling the crespine, though not nearly so delicate. It was woven from natural fibres with the needle knitting technique, so that it resembled a mesh cap with little pieces of square knitting at interlocking sections. At first this was thought to be a bag, but it was discovered in recent years that this was a head piece, worn between 7000-6500 BC in central Europe. This is the first evidence of the article we know as the crespine.

This linen strip under the chin and over the head was called a barbette. The piece that went around the head, similarly to a circlet was called a fillet. The pill box shaped hat was called a coif.

From 1000-1200, braids were the general fashion for hair. Very long hair was essential for the fashionable lady, and there is alot of sculptural evidence to support this. The hair was parted in the middle and arranged in two long braids, falling sometimes as low as the knee. A variation of the normal braiding is the addition of a ribbon entwined with the hair, again seen in numerous statues. A way to lengthen the braids, was to put them in cases, which resembled socks for the hair. These cases were sometimes as high as the neck, and were stuffed with some sort of filling for weight, if the lady's hair was not as long as she wished it to be. The practise of false hair being braded into the natural locks was also used, as there has been archaeological evidence to support this. The braids and the cases were often finished at the ends with one or two ornamental metallic tassels or pearl or bead drops.

Upon the heads of the ladies would be a circlet, or a chaplet of real flowers, or flowers made from gold and precious stones. The head was frequently, although not always, covered with the veil. Loose hair is visible in the manuscript of the Hours of St. Louis, from 1250, Biblioteche Du Roi, Paris. Also loose hair with a simple circlet or pill box style hat, called a coif, is clearly shown in the statues on the left jamb, north portal, facade, Strasbourg Cathedral; The Queen of Sheba, left jamb, right portal, north transept, Chatres Cathedral, 1215-1220; Ecclesia, Strasbourg Cathedral, 1240; and in the illumination Hours of St. Louis, 1250, Biblioteche du Roi, Paris; and as early as the example of a Lady Falconing, from St. Gregory's Moralia in Job, 1110-1120, Dijon, Biblioteche Municipale. Examples of the coif, plaits and crespinette can be seen in the images of the statue Germigny l'Exempt, parish church, west portal, lintel console, 1215-1220; The figures at Chatres Cathedral, 1145-1250; and the statues at Charroux, Saint-Sauveur, former abbey church, 1250.

At the time of Stephen, approximately 1150, uncovered hair and long plaits were at the height of their fashion. The snood, which was the net to confine the hair, was "already worn in ancient times, it was a net used in the 13th century to cover head gear.

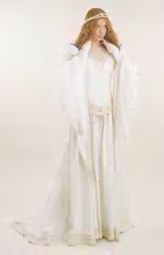

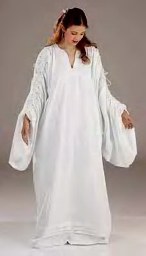

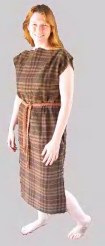

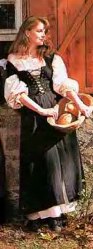

Authentic Medieval Chemise.

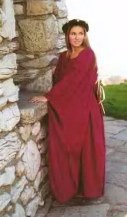

Authentic Medieval Chemise. Early Medieval dress.

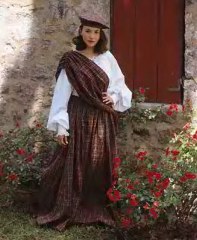

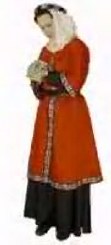

Early Medieval dress. Early Medieval HeadDress.

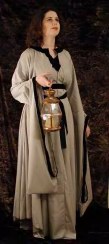

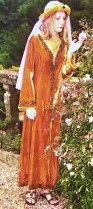

Early Medieval HeadDress. Medieval Braids.

Medieval Braids. Medieval Veil.

Medieval Veil.